Art Cannot Provide a Way Out Favorite

In 2006, art historian Claire Bishop lit a fire under the collective seat of the art world with her Artforum piece “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents.” It set off — as much as any essay in the hermetic and staid world of contemporary art theory can — an uproar. The article inspired Grant Kester, an art historian also specializing in relational art practices, to respond:

“What Bishop seeks is an art practice that will continually reaffirm and flatter her self-perception as an acute critic, “decoding” or unraveling a given video installation, performance, or film … The viewer, in short, can’t be trusted.”

The aggressions towards Bishop were provoked by her cutting critiques of perhaps the most lauded new field of art in the last twenty years. The supporters of “social practice,” or participatory art, contend that we are witnessing a great reshuffling of the old binaries of author/spectator and art/life, leading to democratic and de-alienating possibilities in both art and society. Bishop takes none of this for granted.

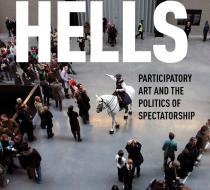

That 2006 article makes up the first chapter of Bishop’s new book, Artificial Hells (the phrase, taken from André Breton, makes arguably the catchiest art-theory book title in memory). Grounded in theater history and Ranciere’s theories of art and politics, Bishop crafts a grand narrative of humans-as-medium in the twentieth century.

The history is organized around the key moments of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, the uprisings of 1968 and the fall of the Eastern bloc in 1989; the political situation is inseparable from Bishop’s aesthetic reading. She includes events and collectives not necessarily included in the discourse of art history, choosing instead projects that address the subjects she foregrounds:

“the tensions between quality and equality, singular and collective authorship, and the ongoing struggle to find artistic equivalents for political positions.”

Bishop’s history is unapologetically selective. Allan Kaprow, for example, makes only a brief appearance as a foil to French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel. The benefit of Bishop’s choosiness is her ability to point out stunning resonances to contemporary issues. The restaging of the Storming of the Winter Palace (Russia, 1920) becomes a precursor to both the mass spectacle of Hollywood war movies and the artist Jeremy Deller’s “The Battle of Orgreave” (2001), discussed a few pages before. Oscar Masotta’s “Group of Mass Media Art” (Argentina, 1966–68) fed a press release and photographs of a “Happening” to major media outlets; after coverage ran, the group issued a statement that no such event had taken place. In today’s media climate, it is hard to imagine a more perfect commentary on media as material and the fallibility of an excitable press.

And no book on participation and performance would be complete without rich descriptions of subversive and offensive pieces, e.g. Jean-Jacques Lebel’s 1962 ‘collective exorcism’ in which “Lebel pushed a pram draped in the French flag weeping ‘Baby, my baby!’ before impersonating a robotic Nazi; an unknown woman got undressed and climbed into a hammock … Lebel leapt across the canvas and out of the gallery shouting ‘Heil art! Heil sex!”

Bishop rejects a premise that grounds much contemporary writing on participatory art: that projects should be evaluated by ethical rather than aesthetic standards. To be reductive for a moment: if a project is about hunger, by the ethical standard it is judged on how many it feeds rather than the questions it raises about feeding. Throughout the book, she does not hide her desire to “keep alive the constitutively undefinitive reflections on quality that characterise the humanities” — to make quality judgments. She uses words like “better,” by which she means the self-reflexive, internally contradictory and morally ambiguous (opposed to clear-cut political stances and sunny utopianism).

She reserves her sharpest words for projects and concepts that fail to advance any progressive project. On Abramovic’s piece requiring performers to kneel at tables at LA MOCA’s gala:

“What is shocking is the performance’s banality and paucity of ideas, and the miserable fact that a museum such as LA MOCA requires this kind of media stunt dressed up as performance art to raise money.”

Or, her ice-cold, one-sentence summary of the state of the commercial art world since 1990:

“ … which has tended to celebrate identity politics, the apotheosis of video installation, large-scale cibachrome photographs, design-as-art, relational aesthetics, conceptual painting and spectacular new forms of installation art,”

all of this filling “a conspicuous lack of what we could call a social project — a collective political horizon or goal.”

The force of Bishop’s language, alternating between biting critique and arching historicization, make attacks on her work unsurprising. But the agitation around Bishop can also be credited to the dullness of the contemporary art discourse, where boosterism is the only form of dialogue and lack of hype around an artist suffices for criticism. Museums, biennials, art fairs and galleries proliferate constantly and seemingly ad infinitum; the expanded field of the curator is discussed everywhere, but without an accompanying rise of the critic.

Bishop’s stances are particularly upsetting for the left. Participatory art seemed as great a promise as any: difficult to sell, engaged with questions of democracy and ethics, challenging the traditional limits of the institution. It is no wonder that much of the dialogue around participation in the last twenty years, which Bishop quotes from and critiques at length, shows not only optimism but excitement. Also no wonder Bishop’s critics dug in the trenches against her.

This which-side-are-you-on problem is exacerbated by Bishop’s harsh assessments of even progressive and constructive projects. She cuts down the community arts movement in 1970s Britain, again with the weapon of aesthetic discernment:

“By avoiding questions of artistic criteria, the community arts movement unwittingly perpetuated the impression that it was full of good intentions and compassion, but ultimately not talented enough to be of broader interest.”

But if we take this with a grain of sugar, we see Bishop’s intention is not to dismiss community arts categorically. Rather, she calls upon such programs to engage in the critical debates that will ensure their lasting resonance.

Bishop’s demanding tone reveals, indeed, a deep investment in the promises and potential of participatory art. The stakes she sets are high enough: in Bishop’s view, participation is nothing less than a quest to escape the “alienation induced by the dominant ideological order — be this consumer capitalism, totalitarian socialism or military dictatorship.” Art cannot (and, in Bishop’s opinion, should not try to) provide a way out. But it can shock, enrage and maybe even delight us into new possibilities, artificial though they are.

Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells (Verso, 2012) is available on Amazon and other online booksellers.