How 'Animal Farm' Gave Hope to Stalin's Refugees Favorite

Reading the introduction to Animal Farm by Christopher Hitchens a few years ago, I was stunned to learn that George Orwell, then a struggling writer in London, worked by letter with a group of refugees to publish the novel in Ukrainian in the displaced persons camps of postwar Europe.

The story of Orwell and the refugees was an incredible triumph of life amidst so much death and destruction. Between Stalin's terror famine and the Gulag, Hitler's concentration camps, the clash of Soviet and Nazi armies in World War II, it was as though hell had opened up across Eastern Europe. Sixty-five years ago this March, Orwell wrote a heartfelt letter to a group of Ukrainian refugees sharing in their solidarity of wanting to expose the incomprehensible evil of totalitarian regimes. The refugees turned the letter into Orwell's only published introduction to Animal Farm, and the only known personal account of how he developed the book that would be considered his masterpiece.

During Orwell's time, information was tightly controlled by a few known names at the top. These were the windmills he quixotically fought against: reading through the lines of mainstream dogma and rubbing the fog off the rosy glasses of his generation overly enamored with Stalin's strength, which they confused with the hopes and dreams of the Russian Revolution. When Stalin's approval rating in the West was at its highest, thanks to cheerleaders with international influence like Watler Duranty of the New York Times, George Bernard Shaw, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, Stalin had already become one of the vilest mass murderers in history with the 1932-1933 terror famine in Ukraine. In this year that Stalin starved to death an estimated 6-10 million Ukrainians, Duranty won the Pulitzer Prize for his spineless coverage of Stalin and the Soviet Union was officially recognized and feted by the United States.

Orwell forged ahead in finding a publisher in March 1944 for his first artistically driven novel, even though, as he said in a letter to a friend, it was "not O.K. politically." Animal Farm was rejected by four publishers, including his usual go-to Victor Gollancz. Jonathan Cape agreed to publish it but then backed out after consulting with "an important official in the Ministry of Information" who, unbeknownst to him, was a Soviet agent. Cape excused himself by expressing his fear that Stalin wouldn't like it. He finally managed to publish Animal Farm with the small press Secker and Warburg that offered him £100.

Animal Farm came out in August of 1945, almost four months after the Nazis surrendered, and by the following February it had traveled east and was read by a young highly educated language and literature scholar 24-year-old Ihor Ševčenko, an unscathed refugee of Ukrainian origin who spent the final years of the war earning a doctorate at a university in Prague. Ševčenko was raised by parents who, during the Russian Revolution, helped lead a movement against the Bolsheviks for Ukraine's independence, and was drawn to the Ukrainian DP camps to help. There, he translated aloud in Ukrainian while reading Orwell's Animal Farm, a book he had recently picked up somewhere, to a transfixed audience. He wrote to Orwell on April 11, 1946, asking if he could publish his novel in Ukrainian for his "countrymen" to enjoy. Orwell agreed to write a preface, refused any royalties, and even tried to recruit his friend Arthur Koestler, author of the Soviet dystopian novel Darkness at Noon, writing, "I have been saying ever since 1945 that the DPs were a godsend opportunity for breaking down the wall between Russia and the West."

In over a year, Ševčenko produced his translation, and worked during the upheaval and violence of Soviet repatriation. The pact Roosevelt and Churchill made with Stalin at Yalta to return Soviet refugees by any means necessary. In the DP camps, American and British soldiers encountered mass suicides and fierce resistance, but managed to repatriate over 2 million Soviet citizens, most of whom were immediately executed or sent to labor camps upon arrival. Luckily, Ševčenko was born in an independent Poland, a nationality that did not fall under repatriation, and just as luckily, printing presses had sprouted up in the DP camps across the American Zone, where he worked.

One in Munich by the name of Prometej—Prometheus in Ukrainian—published his translation of Animal Farm; shipments of the book were quietly delivered to the other camps.

But only 2,000 copies were distributed; a truck from Munich was stopped and searched by American soldiers, and a shipment of an estimated 1,500 to 5,000 copies was seized. The books were quickly handed over to the Soviet repatriation authorities and destroyed.

As for the copies of the Ukrainian edition did survive in the DP camps, they circulated among a population charged with a revived revolutionary spirit. Ševčenko described the Ukrainian DPs to Orwell in a letter, "Their situation and past, causes them to sympathise with Trotskyites, although there are several differences between them." The major difference being a staunchly anti-communist stance.

While working on a screenplay about Stalin's terror famine in Ukraine that, from 1932-1933, starved to death an estimated 10 million people—my grandfather nearly one of them—I read Orwell's Animal Farm for much-needed inspiration. My script was beyond depressing for showing the mass murder Stalin got away with thanks to the help of some of the most brilliant media minds of that era. Upon learning about the Ukrainian translation of Animal Farm, I decided to make it the happy ending to my depressing screenplay about Stalin's famine in Ukraine.

After finishing my screenplay with its new ending, I had dinner at the home of my uncle Vitalji Keis, a retired literary professor for Rutgers, and told him about my project. He had escaped the Soviet Union with his family through the Eastern Front and spent years in the DP camp Heidenau. His first six months in Germany, he lived in a hospital in Hamburg, because he didn't know how to live in the peace and quiet of peacetime. Nine years old, he had developed a constant nervous tick and had to be rehabilitated.

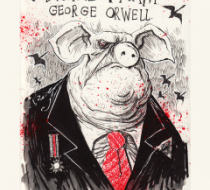

His response to my screenplay pitch was nonchalant, "I have that book. I first read Orwell in the DP camp. We still have it somewhere." My aunt, Tanya Keis, a retired librarian for Barnard College, had also escaped Soviet Ukraine. She jumped up from the table, went into their library, and came back with a copy of Orwell's bootlegged Animal Farm. "Here, this is for you," she said, handing me this thin yellowed delicate pamphlet with a stapled binding. The title read in Ukrainian Kolhosp Tvaryn—the collective farm—an obvious reference to Stalin's forced collectivization enforced by the terror famine. The cover was an earthy red, green, and brown illustration of an exhausted, run-down Boxer the horse pulling a cart in the background, and in the foreground rested a menacing pig, whip in hand. The Orwellian image of one class exploiting the other.

Orwell, this Englishman—a god-like symbol of Western comfort—handed the suffering the light of truth, illuminating their humanity. But as I discovered from research and interviewing members of my family, despite the constant fear of repatriation, a renaissance flourished in the Ukrainian DP camps.

My uncle had first learned about Kolhosp Tvaryn and Orwell in school, where his favorite teacher told his class to read it. So my uncle picked up a copy in the canteen.

But Orwell's masterpiece was just one of many that were bootlegged and distributed in a cultural revival that included traveling theater and ballet troupes, Shakespearian performances in Ukrainian, opera and piano instruction for children, public art galleries with classes and lectures, crafty masquerade balls and dances, pan-DP camp artistic conferences, publications of political and literary journals and libraries full of anti-communist ideology, and a strict school system with scheduled study hours. By the time my uncle immigrated to New York at the age of fourteen, he had already learned calculus, Greek and Latin philosophy, introductory physics and chemistry, botany, and zoology. His DP camp courses were recognized by the state of New York, which required him to only take American history, English language classes, and gym.

"You can't keep intellectuals down," he said. "There were so many artists and creative people [in the Ukrainian DP camps]. Immediately, they started producing."

After five years of living in Heidenau—living the life of an "endless summer camp"—he and his family immigrated to the East Village, and one of the first things they did was help open a literary press.

-

By Andrea Chalupa