How one small Barbie doll took on the art world Favorite

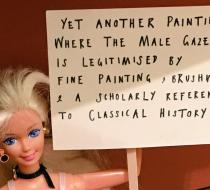

Museums and art galleries are not usually the sites of feminist political protest. Yet over the past couple of years, before the lockdown, gallery visitors all over the UK had noticed a small, determined activist whose modus operandi is “Small signs, big questions, fabulous wardrobe”.

Posing in her most glamorous handmade outfits, ArtActivistBarbie has been calling into question the representation of women on gallery walls, and the lack of female artists in the country’s most prestigious collections. From pointing out that the National Gallery in London has 2,300 works by men and only 21 by women to calling out what she called a “pre-Raphaelite wet T-shirt competition”, the doll has important points to make about the cultural norms we take for granted.

Now that all museums and galleries are closed indefinitely, this whimsical protest which originated in the gallery space is continuing its vibrant life online: sometimes with placards on lollipop sticks (“Refuse to be the Muse!”); sometimes (wo)manning her own tiny information desk.

The woman behind the project is Sarah Williamson, a senior lecturer in education and professional development at the University of Huddersfield. A few years ago, she was trying to find a way to engage her students with social-justice issues and feminist ideas, especially the problematic way women are portrayed in art. She wondered if Barbie, that plastic idealised woman, could become a vehicle for playful commentary on the “patriarchal palaces of painting”. Soon Williamson was gathering a doll army, clothing it in pieces handmade by her feminist mother in the 1970s, with new additions created by her sister. She handed each of her students a Barbie doll and a blank placard on a lollipop stick, then set them loose in Huddersfield Art Gallery.

The resulting mini-protest signs stopped visitors in their tracks, and the photographs of Barbie’s protests drew plenty of notice back in Williamson’s office: “I realised I had something which attracted everyone’s attention and catalysed conversations about how women are portrayed and represented not only in art, but society in general.”

So she set up a Twitter account, @BarbieReports, not really expecting many people to care about this decidedly academic project. “I didn’t even know how to use Twitter,” she confesses. “I was on the train to London and I posted it. And then my phone never stopped pinging the whole week. It just seemed to take off.”

With Mary Beard’s Shock of the Nude having recently aired on BBC2, the authority of art galleries as neutral spaces of culture has been called into question. Beard points out that most female nudes were made for the male gaze, and lines between art and pornography are not easily drawn. Williamson agrees. As she posed ArtActivistBarbie in the Manchester Art Gallery in front of Charles Mengin’s Sappho – which portrays a topless young woman with a sheer drape covering her bottom half – two men approached her. “They said to me that they were realising many of these works were, in their words, ‘Victorian pornography.’”

Visitors are often shocked or amused when they see ArtActivistBarbie. Her playfulness is key to her success, helping to articulate the feminist message in a relatable way. Visitors often take pictures of her, and ask questions about the project.

Williamson remembers one visitor remarking that the Barbies made her “realise just how much women are judged by what’s on the outside and not on the inside”, and this awareness is at the heart of ArtActivistBarbie’s mission. Art museums and galleries exude authority, and the public usually accepts the version of history and culture they portray without question.

“[ArtActivistBarbie] tries to reveal what you don’t always see. She points out what is there, but what’s not there as well. [She tries] to reveal inequality and structures of male power and privilege,” Williamson says. “I suppose she’s a catalyst – helping people to see things with a bit more consciousness … so that people try and look with fresh eyes.”