Iranian Documentary ‘The Gardener', on Religion and Baha’i Garden Favorite

The Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf opens “The Gardener” with the declaration: “I am an agnostic filmmaker.” From anyone else, this might seem like a simple statement, but not from the complex Mr. Makhmalbaf. In 1974, when he was 17, religious and involved in a guerrilla group, he stabbed a policeman, for which he received a bullet to the stomach and a prison sentence.

Freed by the 1979 revolution, he went on to become a filmmaker and restaged the attack in his 1995 movie “A Moment of Innocence.” In that re-creation, though, the assault doesn’t end with one Iranian shooting another, but with a flower and bread supplanting the gun and knife.

That symbolically freighted flower is multiplied a thousandfold in “The Gardener.” An intimate, discursive inquiry into religious belief that opens to include questions about cinema, the movie is largely set within the perimeters of the astonishing Baha’i gardens. Holy sites for the Baha’i faith in the Israeli cities of Haifa and Acre (also known as Akko), the gardens serve as shrines to the Baha’i prophets, Báb, who’s buried on Mount Carmel in Haifa, and Bahá’u’lláh, who’s interred in Acre.

As such they’re kaleidoscopic manifestations of belief, affirmations that have been realized in meticulous, geometric arrangements of hundreds of plants — including towering pines, bright blooms, luscious succulents and gnarled olive trees — and that are intersected by colored paths.

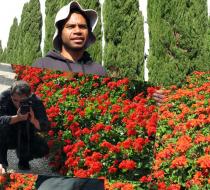

It’s fitting that Mr. Makhmalbaf makes his entrance in the movie on one such path, dressed in dark clothes and walking on a light-colored lane that’s flanked by rows of red flowers and green cypresses, and pierced by an elegant olive tree. He’s accompanied by a second man, his son, Maysam Makhmalbaf, who wears a light-colored jacket. It’s a chromatically striking image that draws attention to the men, and signals other, more significant, differences that will emerge. They’re lugging camera equipment that they will soon use to digitally record the garden, some other visitors and each other during a dialectical exchange on religion, with the elder Makhmalbaf ostensibly arguing on behalf of faith and the younger man more or less presenting the opposing view.

Continue reading the main story

Like the movie, the discussion is soothing, civilized and quietly touching, and because the Baha’i continue to be persecuted in Iran it’s also inherently political. Although he folds in some archival material, Mr. Makhmalbaf pointedly steers clear of contemporary policies and politics and instead focuses on a few Baha’i believers, including Ririva Eona Mabi, a gardener from Papua New Guinea whose mellow words and manner — when he holds a pansy to the camera it’s as if he were cupping a child’s face — verge on the otherworldly. There’s also a woman, an educator of some kind, who’s seen running about with her pink shawl fluttering behind her, an image that’s so embarrassingly goofy and so nakedly sincere that you may feel ashamed for your unkind thoughts, which may be the point.

Who are we to judge? It’s a pressing question for Mohsen Makhmalbaf, who now lives in London, having left Iran in 2005 after the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Even with a new president, it seems unlikely that Mr. Makhmalbaf will return soon, especially judging from the response in Iran to “The Gardener,” apparently the first movie shot in Israel by an Iranian since the revolution.

In July, according to The Los Angeles Times, Mr. Makhmalbaf traveled to the Jerusalem Film Festival with the movie, prompting the head of Iran’s official cinema organization both to denounce him for falling “into the arms of the occupier, the murderous Zionist regime” and to call on the state cinema museum to remove his awards. The visit also inspired letters of support and censure from Iranian intellectuals and others.

The outrage that his visit provoked may seem to have little to do with “The Gardener,” but to separate the movie from its maker and his history would be a mistake. Mr. Makhmalbaf’s radical tolerance is itself an act of political defiance. Given this, it’s worth considering that the English word “paradise” originates in the Persian one for enclosure, pairidaeza.

Mr. Makhmalbaf doesn’t make that etymological connection explicit in the movie, although as he rambles throughout the Baha’i gardens, his camera inching antlike close to the ground and then soaring birdlike over the grounds, he lyrically joins the spiritual with the terrestrial. By the time the movie ends, he has borrowed a gardener’s hat and is tending a holy place that, he has made clear, extends far beyond these enchanted realms.

by MANOHLA DARGISAUG. 8, 2013

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/09/movies/the-gardener-mohsen-makhmalbafs...

link to film:

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thegardener