Waltz with Bashir Favorite

He had served in the army, either as a full-time soldier or as a reservist, for 22 years when he finally decided he wanted out. In 2003, Ari Folman, who had just turned 40, asked his commanders in the Israel Defence Forces to release him from the obligation to do a month's military service every year. They agreed - "so long as you go to the army therapist and talk about everything you went through".

Folman, already an acclaimed film-maker and screenwriter whose service consisted of writing army information films - "How to defend yourself from atomic attack, stuff like that" - began to talk to the counsellor about the most dramatic episode in his military career and one of the most divisive chapters in modern Israeli history: the Lebanon war of 1982. Folman had been just 19.

He realised that he had never spoken about the experience before. "It's not that I had total amnesia about it," he says now, "but I had worked very hard to repress those memories. I had the basic storyline, but there were large holes."

Around the same time, Folman got a call from a friend, Boaz Rein Buskila, a fellow conscript in 1982. In a bar, the rain hammering outside, Boaz told Folman of a recurring nightmare: a pack of 26 vicious, slavering dogs stampede through a smart Tel Aviv street, upturning chairs, knocking over tables. The dream was connected to Lebanon, Boaz was certain. During the 1982 invasion, when an IDF unit tried to enter a village, their presence was often given away by the howling of dogs: Boaz, deemed too sensitive to kill a man, had been given the task of shooting any dogs on sight - to silence them in advance. He had killed 26, and remembered every one of them.

The image had haunted Boaz. Surely Folman had similar memories, similar flashbacks from Beirut? No, Folman realised. Nothing at all. There were vast gaps in his memory - and he became determined to fill them.

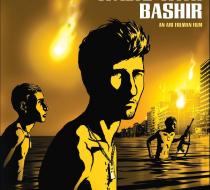

The result is one of the most extraordinary films of this or any year; it is already bagging prizes across the world and building an Oscar buzz. Waltz With Bashir is a documentary, yet it is animated. It tells a series of true stories, yet unspools like a hallucination. It is gripping, painful, and lingers in the mind long after the credits roll. It will surely take its place alongside The Battle Of Algiers and Apocalypse Now as among the very best films about conflict. For it wrestles with two of the great themes - memory and war - and dwells on the collision of the two.

The form is startlingly original. The opening sequence - those hunting dogs - establishes a visual grammar, more graphic novel than kids' cartoon, that is sustained throughout. The figures do not move as they do in the Pixar movies that have raised a generation of children. Instead, they are still, "cut-outs" in which one limb might move while the rest remains static. The effect should be flat, but the low-tech style somehow conveys an emotional depth that catches you by surprise. The characters appear in two dimensions, yet are intensely human.

Not least because their voices are real - not those of actors, but fellow veterans of the war interviewed by Folman. Indeed, it is Folman's voice we hear most often, and we see him in both his 19-year-old and 45-year-old incarnations. In the movie, he speaks to a half-dozen former comrades in arms, along with a therapist friend, a distinguished TV reporter who covered the 1982 war and an expert on post-traumatic stress disorder. It is one of the former soldiers who gives the movie its title: a man, apparently crazed after a long shootout at a Beirut junction, who grabs a weapon from a fellow conscript and begins to fire wildly, as if dancing to some internal music - the entire scene played out before a giant street painting of the Lebanese president-elect, Bashir Gemayel.

The climax of the movie, and the heart of Folman's missing memories, is the massacre at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. Enraged by Bashir's assassination, Christian Phalangist gunmen went on the rampage, murdering hundreds if not thousands of Palestinian men, women and children. (Estimates of the death toll range from 700 to more than 3,000.) Folman finally remembers that he was among the IDF men ordered to launch flares into the night sky over the camps. According to Israel's own Kahan commission of inquiry, the "illumination" was requested by the Phalangists to help them in their grisly work - though Folman is emphatic that at the time he and the soldiers beside him "had no clue what was going on: we didn't know there was a massacre".

Those events prompted a bout of introspection in Israel that has rarely been equalled. An estimated crowd of 400,000 gathered in the centre of Tel Aviv to protest. Since that represented one tenth of the entire Israeli population, proportionally at least it can claim to be the largest political demonstration in any country at any time. Kahan found the then defence minister Ariel Sharon bore "personal responsibility" for the Palestinian deaths and concluded that he was unfit to serve in the defence ministry (though it did not stop him becoming prime minister 19 years later).

All of this would have made compelling material in a conventional documentary, even a drama-documentary involving actors' reconstructions, but Folman never doubted that this film would have to be animated: "There was no other way to do it, to show memories, hallucinations, dreams. War is like a really bad acid trip, and this was the only way to show that."

Once you see the film, you know what he means: Carmi Cnaa'n recalls the boat ride that took him to Lebanon, how he threw up, how he then fell into sleep - "I sleep when I'm scared" - only to dream he was rescued by a voluptuous giantess, who held him like a nursing mother as she swam away from the vessel just seconds before it was bombed from the air. In a live-action movie, such a scene would have been impossible - or absurd.

Driving the story is Folman's own quest to recover his memory, guided by his best friend-cum-therapist. Was the making of the film an act of therapy in itself? "It was like scratching an old scar, an old wound," the director says, sitting in New York for yet another film festival, receiving another round of plaudits. "The memories spurted out."

And not only for him. Perhaps the most striking sequence in the film tells the story of Roni Dayg, today a lab chemist for an Israeli dairy company. Back in 1982 he was a tank loader when his unit came under fire. He and his comrades fled the tank, carrying no weapons, and were picked off, one by one, by Palestinian snipers concealed in the surrounding buildings. By the time Roni reached a rock and hid behind it, the rest of the men were dead. He waited, gasping for breath. The minutes passed until the snipers emerged, some of them just yards away from Roni. Somehow they never noticed him.

He waited for nightfall, then ran towards the beach. With no clear plan, he plunged into the water and swam. And swam. And swam. An explosion struck nearby, rippling out across the water. But Roni kept swimming. Eventually, exhausted, he reached shore again. Who knew by then where he was? (In fact, despite swimming for six hours, he had covered only six kilometres.) He heard voices: they could have been Israelis, they could have been Lebanese. But the language was Hebrew. Incredibly, he had reached his very own regiment, finding them in the place to which they had retreated. He staggered on to the beach and was saved.

When I speak to Roni Dayg, he concedes the strangeness of seeing the most traumatic moment of his life drawn and animated on a big screen. But he is relieved, too. For years, he explains, he had felt awkward with the loved ones of those soldiers killed beside the beach, as if they somehow resented Dayg for having survived, as if they believed he had saved himself at his comrades' expense.

"I couldn't look at their families," he says. "I felt responsible. Now, with this film, it's all out. This shows what happened." He's had calls from old friends, people he hadn't seen for years. "And that feels good."

The relief is not confined to those featured in the movie. Waltz With Bashir seems to have released something long pent up among veterans of Israel's least celebrated war - described at the time as the country's first "war of choice". The film's makers say they are now constantly buttonholed by men in their 40s desperate to tell their stories of Lebanon. According to art director David Polonsky, "You realise that they've been walking around for 25 years with this life-changing experience and they've never talked about it."

This focus on the experiences of IDF veterans may bring grumbles from some of Israel's critics. Isn't Waltz With Bashir asking us, however artfully, to sympathise with the invaders of 1982, not the invaded - to somehow see the IDF, rather than the Lebanese and Palestinians of Beirut, as the victims of that war?

It is not a new criticism. The spate of American antiwar movies about Vietnam were also faulted for casting young US draftees as the central casualties of the conflict, rather than the Vietnamese themselves. But there is a peculiarly Israeli dimension to the objection, too. In Hebrew they speak of "shooting and crying", shorthand for the tendency to depict the Israeli soldier as morally conflicted, the reluctant warrior whose heart is broken by having to kill his enemy. Such an archetype runs through Israeli folklore and can be seen as a mechanism that allows Israelis to emerge from even their darkest episodes with their moral self-image intact.

Folman was fully alive to this risk, but is adamant that Waltz With Bashir does not succumb to it. "When you watch this film, you have no doubt who the victims are." He says it's impossible to have sympathy for the IDF soldiers when you see the impact of their invasion - and this film certainly shows that impact, from the casual trashing of Beirut streets to the eventual carnage of the refugee camps.

Indeed, the catastrophe at Sabra and Shatila is given a weight that sets it apart from the rest of the film. In the final minutes, animation gives way to real-life video footage of the slaughtered - including one unbearable image of a child. In this sense, the Palestinian dead are given a three-dimensional realness denied everyone else.

Should Folman have gone further and told Palestinian stories with the same close humanity he gave to himself and his fellow Israelis? He considered it, wondered about making a "Rashomon" of 1982, showing the conflict from the differing viewpoints of all those involved. But it was not for him. "Who am I to tell their stories?" he says of the Palestinians. "They have to tell their own stories." Not that Folman believes Waltz With Bashir conveys only a narrow Israeli experience. There is a universal lesson to be drawn from his film. It is that war is not Platoon or Steven Spielberg's Band Of Brothers: "It has no glory, no glamour, no bravery, no brotherhood of men, nothing."

Perhaps the most surprising frame of the entire movie is one of the very last: a fleeting acknowledgment of support from Israel's culture ministry and film board. Folman says that when Waltz With Bashir has played at festivals in cities around the world, local Israeli embassies have embraced it.

It's an unexpected reaction, given the unflinching depiction of Israeli brutality, IDF soldiers shooting and shooting even when they have no idea who they are shooting at. And yet it's not so hard to understand. For one thing, the Israeli soldiers in the film have had their humanity restored to them: they are not faceless killing machines but terrified young boys.

More importantly, perhaps, the film is at great pains to make crystal clear what has long been murky: exactly who did what at Sabra and Shatila. Again and again, Folman's script stresses that the massacre was committed by Christian Phalangists (who even slashed crosses into the chests of their victims). The publicity material quotes Folman thus: "One thing for sure is that the Christian Phalangist militiamen were fully responsible for the massacre. The Israeli soldiers had nothing to do with it." That act of clarification is probably reason enough for Israeli officialdom to have welcomed the film.

But there is much to give them discomfort. Sharon himself is shown tucking into a massive cooked breakfast - including five fried eggs - while the killing goes on all around. Later he is notified by phone that a massacre is rumoured to be underway: he thanks his informant and does nothing. That is one of the few flashes of political anger in the film. Elsewhere, there are no statements or polemics, even though its story was given new resonance as production got underway in the summer of 2006 - with the outbreak of the second Lebanon war. Polonksy, the art director, recalls that any illusion that he and his team of animators were working on a mere "artwork" was shattered. "It was happening in real time again; the same stupidity all over again."

Could Waltz With Bashir move Israeli hearts and minds so intensely that it prevents a future war? None involved thinks so. "Cinema doesn't change the world," they say. But for those who where there, they have performed a service. "None of us spoke about this war," says Folman. "I've tried to open things up."