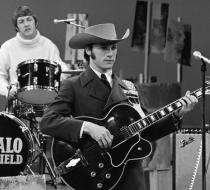

For What It's Worth, Buffalo Springfield Favorite

Released as a single on 23 December 1966, Buffalo Springfield’s For What It’s Worth became the short-lived but talent-packed band’s biggest hit, reaching No.7 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the spring of 1967. Even so, its impact transcended sales and chart positions: For What It’s Worth became one of the defining songs of the 60s, a countercultural anthem that captured a moment of genuine change in society and emphasised the growing generation gap in the postwar era.

Songwriter Stephen Stills’ lyrics (“Young people speaking their minds/Are getting’ so much resistance from behind”) reflected a time of division, of an increasingly empowered youth railing against the establishment. Following its release, For What It’s Worth quickly became adopted as an anti-war anthem – unsurprising, given that it was written at a point when public unease over the US’s involvement in the Vietnam War was rapidly growing. But the incident that sparked the song was much closer to home.

The 60s saw the rejuvenation of the Sunset Strip, in Los Angeles. Many of the larger clubs and restaurants in the once-affluent area had closed in the 50s and early 60s. Rents fell and coffee houses, jazz clubs and, eventually, rock’n’roll venues could now afford to move into the area, which soon became hip among a younger, trendier crowd.

With the opening of the Whisky A Go Go, in January 1964, the Strip exploded, with scores of clubs popping up in its wake. “There was a string of nightclubs on the Sunset Strip from Crescent Heights to Doheny, maybe 25 clubs with live bands every night, and there was a whole movement of people that went there every night and walked up and down Sunset – hundreds and hundreds of people,” manager and record executive John Hartmann explained in the book Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story Of Rock-And-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood.

The Doors, Arthur Lee’s Love, The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield all cut their teeth on the strip, as the area became rock music’s epicentre; by day, its fast-emerging boutiques drew fashion-conscious hippies. Local landowners and the Sunset Strip Chamber Of Commerce were not amused by the long-haired hordes and, in 1966, successfully applied pressure on the county sheriff’s department to apply a 10pm curfew for teenagers.

“THOUSANDS OF KIDS HAD GUITARS. IT STOPPED TRAFFIC FOR MILES”

A protest was planned for 12 November 1966, and, initially, it was as peaceful as the organisers had expected. “We sat, cross-legged, in the street, Sunset Boulevard, holding hands and singing,” performer Pamela Des Barres later told Vanity Fair. “Kids had guitars, thousands of kids, it stopped traffic for miles on either side of Sunset.”

At curfew, law enforcers made aggressive moves to end the protest. “At 10.35pm, the officers, many in helmets, began a sweep and clear operation. Advancing along the sidewalk in a column of about fours, they pushed bystanders out of the way, sometimes using nightsticks,” reported the Los Angeles Times. “The police, tempers visibly short, ordered everyone to leave the area.”

It was at this point that Stephen Stills arrived on the scene. “I had a house in Topanga. Me and a friend went over to Laurel Canyon to go clubbing,” Stills told American Songwriter in 2019. “We were young and bored. We came to Sunset Boulevard. On one side was this whole battalion of cops. In full Macedonian battle array… we got out of the car to see what was happening, and there was this funeral for [the club] Pandora’s Box that was spilling out onto the street. And the cops just went nuts. So I said to my friend, ‘Get me back to my guitar.’”

“I WROTE IT IN ABOUT 15 MINUTES. EVERYONE LOVED IT”

It was a shrewd move on Stills’ part. Fired up by the evening’s events, the Buffalo Springfield co-founder wrote For What It’s Worth. The song was simple, soulful and direct, with lyrics that could be applied to a general feeling of malaise (the opening lyric was an all-time great: “There’s something happening here/What it is, ain’t exactly clear”) while making literal references to the disturbance Stills had witnessed (“A thousand people in the street/Singing songs and a-carryin’ signs/Mostly say, ‘Hooray for our side’”).

Stills would later tell American Songwriter how quickly the song came together, from writing to release: “I wrote it in about 15 minutes. Everyone heard the song and loved it, and Ahmet [Ertegun, co-founder of Atlantic Records] said, ‘You have to record it.’ We had a record in the pipeline [Buffalo Springfield’s self-titled debut album], and he said, ‘Stop the presses,’ and we had it out in seven days… which is a trick that people have been trying to replicate ever since.”

As for that tile, Buffalo Springfield singer and guitarist Richie Furay later claimed that it came about when he, Stills and guitarist/vocalist Neil Young played new material for Ertegun: “We were at Stephen’s house and at the end of the day, Stephen said, ‘I have another one, for what it’s worth.’”