Drawing the line: meet the Romanian artist-activist tackling world crises one cartoon at a time Favorite

Dan Perjovschi is one of Romania’s foremost artistic voices. Although known as a talented multi-disciplinary artist in his home country, particularly for his early performance work, he is most widely known internationally for his massive drawing installations. Executed directly onto the walls of buildings, public spaces and gallery walls using simple chalk or marker pens, these figures and shapes reveal a wry and playful sense of humour, while at the same time demonstrating his sharp critical focus. Simple stick figures or sketches are used to articulate fantastically nuanced critiques of both domestic and international politics and culture, something which has been particularly obvious in current works dedicated to the refugee crisis in Europe.

At a recent exhibition in Timisoara for example, one work contained two figures; the first was carrying a child next to the word “real”, the second carried a bomb with the word “fear”. It’s a commentary which feels particularly poignant after the recent attacks in Paris. Elsewhere, he illustrated the changing tides of political focus, writing “EU’s Problem: Syriza Syria” to reflect the unpredictable priorities of the continent’s governing bodies. It’s the careful combination of humour and criticism which has made him such a central figure in Romania’s art world, particularly his enthusiasm for encouraging younger artists and contributing drawings to protests and student demonstrations.

Perjovschi’s drawings have appeared in the walls of museums such as Tate Modern, London, The Ludwig Museum, Koln and MACRO in Rome to name just three, and since 2010 he has undertaken a project called Horizontal Newspaper in his hometown of Sibiu. Each year he spends time drawing new images along a massive stretch of public space, to which he later adds or subtracts, updating the focus of his images as global news dictates. His drawing is a personal response, but within this is a strong activist sentiment that shouldn’t be understated.

When speaking with Perjovschi, there is a clear connection between his current practice and the difficult roots of his career in the 1970s and 1980s in Romania, something he underscores by emphasising that the year he was born, 1961, was the same year the Berlin Wall was erected. More to the point, he adds, he was “born on the wrong side of it”. Even now, 25 years after the fall of communism in the Eastern Bloc, there’s a sense that he still doesn’t take anything for granted. When I ask him about this directly, he’s frank in his response.

“It’s a fantastic situation. I am given a wall in a big museum, or a room or a space some place, and I can articulate on that territory whatever I want…I remember the moment when I could not do that.” That situation also carries with it a certain obligation, something about which Perjovschi is equally matter-of-fact, “I feel a bit that I have a responsibility that me as an artist, now, I am given a territory to talk. So I talk.”

As we discuss his career after December 1989, Perjovschi’s relationship to media and press comes more sharply into focus. “My drawing is more related to the newspaper, you know, editorial, like graphic editorial. Much more news-based,” he tells me. “I look at things as a journalist.” It was the ability of the media and press to rapidly adapt to the changing landscape in Romania that made it an engaging platform on which to explore his ideas, he explains. His work at Revista 22 magazine, launched a month after the revolution that overthrew Ceausescu and to which he still contributes work and editorial comment today, very much helped frame his work. “The weekly magazine where I work is political, social, and cultural. So my drawings are like that on the wall.”

It’s undoubtedly a vantage point that lends his work a sense of timeliness and critical awareness, as well as longevity. Some of the images are ingeniously simplistic, yet many carry a universality that allows them to be applied multiple times across multiple venues. Perjovschi has a core set that he returns to, something he likens to a band pulling out their classic hits during a concert when appropriate; simple faces, bodies with legs and no arms, unassuming symbols to articulate complex issues in a relatable way. There is also a noticeable shift in their execution that speaks to a growing confidence the artist has in the languages he has developed over the course of his career, both in his drawing and his humour. “My drawing just grew, the line became more thick and the drawing is more brutal.”

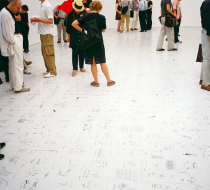

A major breakthrough in this evolution came with his selection to represent Romania at the Venice Biennale in 1999. Perjovschi covered the floors of the exhibition space with images organised in a grid, which over the course of the Biennale started to fade as visitors walked across the space. “I did a grid on the ground, and then people step on the grid and kind of kill it,” he recalls. The erasure of the grid left images hanging in space, something which has become a hallmark of his work since. “I saw this possibility…everything I show today was this. I learn from me showing, and things happening to them.”

Perjovschi’s works also beautifully encapsulate an idea expressed during our discussion that “solidarity is complicated”. “I’m in favour of freedom of expression, and even the freedom to become insolent, offensive,” he says, adding “I don’t do that in my drawings. I try to create bridges, so I cannot be nasty on purpose.” His work in response to the attacks on the offices of Charlie Hebdo is a good case in point. For him, perhaps the crucial element of the attack was the story of Ahmed Merabet, the 42 year old Muslim police officer gunned down outside the offices of the publication that was attacked for satirising his faith. “I was strongly emotionally involved,” Perjovschi tells me, “but my statement was Je Sui Charlie et Ahmed.” This phrase was central in a small newspaper pressed during an exhibition in France not long after the attack.

The artist’s outspoken objection to the National Museum of Contemporary Art being housed in the massive Parliament Building built by Ceausescu is another common topic of debate, and in fact the inspiration behind a series of works shown as part of his intervention at CEREFREA Villa Noël during Bucharest Art Week in October this year. A selection of gaudy postcards of Bucharest city vistas had all had the Parliament Building blacked out with marker pen, an expression of Perjovschi’s disdain for the location, and the fact that people must now pay an entry fee to see the gallery housed in one of its wings. Having sacrificed so much already, he sees no reason for citizens to have to pay anything more, and refuses to show work in the space (a sentiment shared by several others in Bucharest’s art scene).

In the above cases as in others, Perjovschi is respectfully but steadfastly unapologetic in his views. His work continues to highlight the hypocrisy of Europe’s migration laws, and the influence of the market in political decision-making, while remaining critical of those who selectively reminisce about Romania’s difficult past. It’s a reflection once again of the path he has had to take to get to where he is, and the overriding responsibility he feels as both an artist and a journalist to reflect the society he is living in, with all the good and bad that that entails. As Perjovschi himself acknowledges, it’s complicated.