Habla, pueblo, habla: Advertising techniques for (a sort of) political change Favorite

On Wednesday, December 15th 1976, a referendum was held in Spain. The question was to pass or not to pass the Ley para la Reforma Política (Political Reform Act). This Act was the legal instrument that allowed Spain to transition between Francisco Franco’s dictatorship to a democratic constitutional regime, a parliamentary monarchy.

Franco had died in 1975, leaving the King Juan Carlos I as the head of the State. He was the one who designated Adolfo Suárez as President in 1976. Adolfo Suárez’s government was under a lot of pressure: On one side, what is commonly known as “el búnker” (“the bunker”), this is, the most conservative, extremist faction of francoist regime, wanted the situation to remain the same. On the other side, the democratic opposition to the regime claimed for a radical rupture, for the condemnation and prosecution of francoist crimes and for the reparation of the victims. This tension, that would burst in the coup d’état on February 23rd 1981, was starting to be unbearable for the provisional government, and certain groups started to fear a new civil war.

In this climate, Adolfo Suárez needed the Spanish citizenship to pass the Political Reform Act. He was not only a charismatic leader, but had also been in charge of RTVE (Radiotelevisión Española, the Spanish public broadcasting network) from 1969 to 1973. He was conscious of the power of mass media and advertising, so he designated the publicist Rafael Ansón as RTVE director so that he would use his expertise for the campaign.

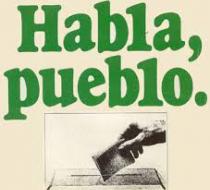

Most of the advertisements were in form of short, simple messages, but there is one that stood out. “Habla, pueblo” (“Speak, people”) was the slogan that became the motto of the campaign, in form of graphic propaganda, a radio jingle and a television spot. This slogan references a song with the same title. The band “Jarcha” made it popular, to such an extent that even today the generations that could vote for that referendum still remember it.

These were the lyrics of the song: Habla pueblo habla / Tuyo es el mañana / Habla y no permitas / Que roben tu palabra / Habla pueblo habla / Habla sin temor / No dejes que nadie / Apague tu voz / Habla pueblo habla / Este es el momento / No escuches a quien diga / Que guardes silencio / Habla pueblo habla / Habla pueblo sí / No dejes que nadie / Decida por ti

And this is the translation into English: Speak, people, speak / Tomorrow is yours / Speak and don’t let anybody / steal you word / Speak, people, speak / Speak without fear / Don’t let anybody / Shut down your voice / Speak, people, speak / This is the moment / Don’t let anybody tell you / To keep in silence / Speak, people, speak / Speak, people, yes / Don’t let anybody / Decide for you.

This was the first time in Spanish history when a political group (the provisional government and other organizations favorable to the Political Reform Act) used advertising techniques and aesthetics to deliver a political message. Participation in the referendum was 77,8%, and 94,17% of the votes said “yes” to the Reform.

A year later, Adolfo Suárez’s political party, UCD (Unión de Centro Democrático – Democratic Center Union), used the same song for his presidential campaign.