The Role of Graphic Novels in Social Activism 2 Favorite

By Jessie Blaeser

Graphic novels occupy a strange space. They exist somewhere in between the literary world and a childlike obsession with images, as they provide an illustration of the action right on the page so that the mind is not strained to produce one. Readers of graphic novels know, however, that despite seeming simple, the medium can elicit complex and moving stories, only bolstered by their ability to take advantage of two forms of expression rather than one: images and words. Rather than ease a reader’s contemplation of a storyline, images in graphic novels challenge readers to think beyond the page. When the imagination does not have to work to produce a visualization of the action in the novel, it is freed to look deeper into the meaning behind those actions and the themes surrounding them. As a result, graphic novels’ thematic focus on political and social movements is all the more effective due to the forms in which their creators have chosen to tell their stories.

Comic books have circulated throughout the United States and Europe over the last century. Their protagonists are colorful, strong, and benevolent﹘and most of them have supernatural powers. Superman hailed from Krypton, Batman’s billions enabled him to create his own bat-persona, and Wonder Woman is both a demigoddess and a warrior princess. These characters and more comprised The Golden Age of Comic Books during the 1940s, but after WWII came to a close, children found that they did not need god and goddess-like characters to demonstrate ability, safety, and power. Instead, children’s imaginations turned to comics that fulfilled new genres: Westerns, Science Fiction, and Romance to name a few. Even so, one theme flourished throughout comic books everywhere, no matter what their story focuses on: justice for all.

The superhero waned, as did comic books in the ensuing decades. Comic books became items of nostalgia for adults, and for the kids that still held an interest, comics were a niche market; understanding of the medium remained only behind comic book store doors and hardly ventured into the walls of classrooms and universities. The literary world looked down upon the comic books that helped so many young readers cope with the massive war that wiped out 60 million of their fellow humans. Someone from Krypton﹘someone who was immune to the death and pain tearing through the land﹘needed to be there in order for hope to survive. Rather than study how the comic-form helped achieve this, critics and academics wrote off the genre and siloed it into one reserved for kids with superhero fantasies.

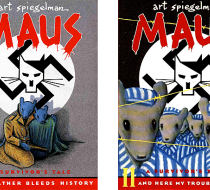

That is until a graphic novel won a special citation Pulitzer Prize in 1992, the first of its kind to receive substantive attention in English-speaking countries. Art Spiegelman’s Maus series blended the familiar graphics of comics with memoir, biography, and historical fiction. In doing so, Maus covered Spiegelman’s father’s experience in the Holocaust. The term “pictorial literature” was born and suddenly graphic novels﹘named such to separate the medium from its comic book predecessor and imply greater length and complexity﹘disrupted literary thought and provided a new medium for authors.

But Maus had another element to it. The characters in the novel are not super﹘they are not even human﹘they are mice and cats. Spiegelman said that he had an epiphany in which he realized the cat-mouse metaphor had bearing on his own life, and upon further research, he discovered that the association between mice and Jews during 1940s had already been secured. Spiegelman found Nazi propaganda depicting Jews as rats with large noses, calling them “the vermin of mankind.” Furthermore, he found that a chemical used to kill vermin was also used in Auschwitz as a killing agent, and thus, the connection between the Jewish characters in Maus and their mice personas became clear.

In this sense, Spiegelman’s series seems to evolve from a greater pictorial history than even that of comic books; by using cats, dogs, pigs, and mice to demonstrate different groups of people within WWII, the book is a nod to political cartoons. Where comics are fantastic and straightforward, political cartoons are grotesque and elicit greater thought. The caricatures of Jews created by the Nazis were the very thing that inspired Spiegelman to pursue the cat-mouse metaphor in telling his and his father’s story through visual allegory, and as such, his novel hints back to a greater history that uses exaggerated features and animals to drive a point.

Comics, political cartoons, and now graphic novels. They all use images and text to tell their stories, and with Maus’s breakthrough in the market, they have one more key commonality: each involve some form of political commentary. The Golden Age of Comics did not necessarily incorporate multiple schools of political thinking, but they did produce one side of political thought aligned with the Allied Powers. A main objective for superheroes of the 1940s was after all to demonstrate that the Allies could beat the Axis Powers, and although they were not meant to spark political discourse, they were inherently associated with justice for the weak and victory for those who help them. Political cartoons, on the other hand, have an obvious association with politics, but where comic books focus on justice, political cartoons challenge the fabric of our political reality. And now, graphic novels use similar tactics to create political conversations. In this sense, the combined use of images and words for political and social commentary becomes a storied tradition revitalized by graphic novels’ entrance into the literary market.

This longform version of what generations before us craved has formed its own following in the decades since Maus was published. Students study graphic novels in classrooms and bookstores dedicate primetime shelf-space to the finest of the medium. Graphic novels can tell stories about anything, just like any other book, but the most popular ones still focus on topics regarding political and social movements.

It is no coincidence that the novels voted to be the “Best Political-themed Graphic Novels” on the popular lit review site, Goodreads, also claim top spots on the more general list of “Best Graphic Novels.” The general list is broadened by the addition of superhero and science fiction titles (some of which are also political in nature). The graphic novel genre is brimming with political commentary, which begs the question as to whether or not the graphic novel was simply the natural evolution of a medium dedicated to justice? Our modern focus simply moved crime and war-fighting justice into a social justice framework. Originally, the medium’s focus was on political justice and activism. And today, we are seeing more graphic novels with social justice in the spotlight.

More recent graphic novels like Congressman John Lewis’s March (2013-16) and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006) challenge notions of modern civil rights and domestic life, respectively. The March trilogy covers the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and is told from the perspective of civil rights leader and Georgia Congressman John Lewis (of Atlanta’s now famed 5th district). The series starts in Selma on Bloody Sunday in 1965 and moves through Brown v. Board of Education, the Freedom Riders, and the Freedom Vote. Fun Home, on the other hand, is a standalone piece﹘ adapted into a Tony Award-winning Broadway musical in 2013﹘covering Bechdel’s own childhood and early adulthood. The graphic memoir subtitled “A Family Tragicomic” looks back on Bechdel’s relationship with her father. In the memoir, Bechdel discusses coming out to her parents, discovering her father’s homosexuality, their shared dissatisfaction with their prescribed gender roles, and a slew of other themes relating to family dysfunctionality, emotional abuse, and suicide.

Although March and Fun Home present different topics, time periods, and even artistic styles, at their core they are both representative of sociopolitical topics and movements; March of civil rights and Fun Home of the modern LGBTQ+ family experience. In this sense, the superhero we once looked to for guidance has evolved into the political warrior and political commentator of the social experience. Rather than flee reality and fight fictional monsters as superheroes do, the characters in these graphic novels fight monsters who are very much real; fights of claws and fists turn to ones of laws, discrimination, and schools of repressive thought.

Graphic novels are by no means the only written or visual medium used for political commentary. Artists have been discussing the political climate through their chosen forms for centuries, which begs the question as to whether or not the graphic novel is different from the rest. Do graphic novels yield some sort of special ability since they use both visual and written means of expression?

Marjane Satrapi’s The Complete Persepolis (2000) provides some answers. Satrapi’s black and white, simplistic cartoons detail her experiences growing up in Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The reader follows Satrapi as she tries to navigate the cultural changes that take place in her life after the revolution; she is suddenly obliged to wear a veil and is separated from her male counterparts. The memoir weaves through Satrapi’s eventual rebellion against her upbringing, developing themes of personal growth, education, and the struggles of finding yourself. After she leaves Iran due to her lack of opportunity there, she returns years later and begins to understand what her parents endured while she was away. Satrapi’s book demonstrates a child and young adult’s perspective on life after a civilization is turned sideways due to a political change, which will have innate social ramifications. This type of change is not something that everyone experiences in their lifetime, so when it does happen, it’s nearly impossible to visualize. Thus, Satrapi invites her readers to face a very real monster that they may never have encountered before.

The graphic novel allows us to not just read, it allows us to see. Rather than conjuring our own mental images of the stories we read, we are placed in the scene by the author his or herself. Graphic novels leave little room for interpretation or disagreement when it comes to our author’s visualisations of their circumstances.

In each of these novels, the main character’s world is turned upside down by something outside of their control. In Maus, a son recreates his father’s survival in the Holocaust through visual allegory. In March, an activist demonstrates what it looks like to take a stand for your people and create change. In Fun Home, a daughter copes with her identity and unearths her family’s real story once she’s reached adulthood, making strides for the LGBTQ+ community and for lesbian representation. And in The Complete Persepolis, a young girl lives through a changing regime and learns how to preserve her identity despite what she is obligated to do by her government, revolutionizing the way many people view the Middle East. Each of these stories demonstrate how to cope and fight for what the characters or authors want or believe. In this way, the superheroes of the past have indeed become the social activists of today, now telling their own stories rather than leaving that responsibility to the imagination of others. The evolution of the comic book produced a medium with a similar thematic focus on justice, but beyond even that, created a different type of story-telling. Readers can now both read and see the story, which frees the mind to focus less on the interpretation of events and more of the effects and consequences of political and social movements.