Tupac's “Changes” Favorite

Late last year, the New York Times published an op-ed short film written and narrated by Jay Z. The clip was called “The War on Drugs Is an Epic Fail,” and that kind of title was explicit enough for everyone to grasp the entertainment mogul’s general argument, whether they knew anything about drug war or not. In a quick three minutes and 58 seconds, Jay Z’s script dismantled the United States’ prohibition campaign from its conception during the Nixon administration to the systemically oppressive role it continues assuming half a century later. The War on Drugs is very alive and even more underdiscussed; regardless of what any convoluted, regressive thinker insists, Jay Z’s arresting critique is necessary and relevant.

Although, one shouldn’t expect anything less than well-versed street smarts from a crack dealer-turned-bestselling rapper-slash-multimillionaire – indeed, for the delivery of this message, Jay Z was the perfect man. All the while, the video was capable of prompting nostalgia within those who experienced American society while racist politics faced a growing threat: hip-hop that told people to fuck the police and fight the power, courtesy of acts like N.W.A and Public Enemy.

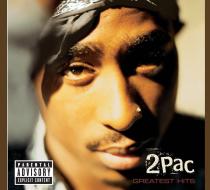

Posing as an even larger threat were conscious raps with cleaner pop hooks – these were the tracks given airtime on mainstream radio, reaching the masses without (too many) bars falling victim to censorship. Today, Tupac Shakur’s posthumous single “Changes,” featuring Talent (via Death Row in 1998), should be observed as one of hip-hop’s most successful political statements, not because it’s especially radical in its words on police brutality, drugs and gang violence, but because the track was, from music to lyrics, accessible to those who needed it – people unconcerned with the politics challenged by unapologetic MCs.

Consider “Changes” as late-20th century memorabilia, the variety that sparks dramatized car sing-a-longs or kid recollections of cleaning the house on a Saturday morning, yearning to enjoy the sun’s warmth outside. In this way, Shakur’s track is not dissimilar to its politically charged successors like Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” or, more recently (and perhaps subtly), “Neighbors” by J. Cole. All three cuts have ironically become anthems of hope or humor – especially “Alright,” which, despite its canonical role as a serious review of police brutality and communal black solidarity, rouses a crowd of smiling faces like no other. Moreover, the denouement of “Neighbors” (Cops bust in with the army guns / No evidence of the harm we done) censures the foolishness of both a notional “post-racial society” and racial profiling through narrative humor.

Then there’s “Changes,” built atop a depressive anger that Shakur never shied from touching: “I see no changes, wake up in the morning and I ask myself / Is life worth living, should I blast myself?” Manifestly, the 1998 track wasn’t really about suicide. It was entirely about the problematic conditions that could lead someone like Shakur – a targeted black man in “post-racial America” – to consider committing such an act. Still, the misery and inequity (“Take the evil out the people, they’ll be acting right / ‘Cause both black and white is smoking crack tonight” and “It ain’t a secret, don’t conceal the fact / The penitentiary’s packed and it’s filled with blacks) lyrically represented in “Changes” signaled awareness, even as it signaled a discouraging reality.

I see no changes wake up in the morning and I ask myself

Is life worth living should I blast myself?

I’m tired of bein’ poor and even worse I’m black

My stomach hurts so I’m lookin’ for a purse to snatch

Cops give a damn about a negro

Pull the trigger kill a nigga he’s a hero

Give the crack to the kids who the hell cares

One less hungry mouth on the welfare

In fact, beyond words, it had potential to achieve a goal of encouragement and cognizance more so than its successors because of its foundation – a soft rock cut that skyrocketed to the peak of the Hot 100 back in 1986 called “The Way It Is.” Written by Bruce Hornsby (and performed by Bruce Hornsby and the Range), “The Way It Is” wasn’t sampled just because of its pleasing piano solos, drum machines or a coincidentally germane chorus of concession, “that’s just the way it is” – those qualities could be found in more than a hundred other older pop hits, all of which would be restored to radio gold if united with the rhyme of Shakur’s exasperated timbre.

I see no changes all I see is racist faces

Misplaced hate makes disgrace to races

We under I wonder what it takes to make this

One better place, let’s erase the wasted

Take the evil out the people they’ll be acting right

‘Cause both black and white is smokin’ crack tonight

And only time we chill is when we kill each other

It takes skill to be real, time to heal each other

And although it seems heaven sent

We ain’t ready, to see a black President, uhh

It ain’t a secret don’t conceal the fact

The penitentiary’s packed, and it’s filled with blacks

But some things will never change

Rather, beneath the catchiness and identifiability of the Hornsby sample is lyrical meaning centered on the issues that came right before the birth of a failed drug war that folks like Jay Z refuse to forget – racial segregation, individual prejudice and discriminatory public accommodations. “Well they passed a law in ’64 to give to those who ain’t got a little more / But it only goes so far, ‘cause the law don’t change another’s mind / When all it sees at the hiring time is the line on the color bar,” sings Hornsby, in reference to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This is not to say that Hornsby was some comprehensive sage of Civil Rights Movement – he was a white man with a piano and debut single to record, using his influence to speak to an audience that probably deserved a wake-up call rougher than gentle keys and crooning. But there was something special shared between Shakur and Hornsby: a sense of conscious artistry serving to acknowledge, protest, and hopefully defy black oppression via popular music.