Walden, A Game Favorite

It’s certainly a long way from Grand Theft Auto. Henry David Thoreau’s classic “Walden” is the inspiration for what Smithsonian Magazine is calling “the world’s most improbable video game”: Walden, a Game.

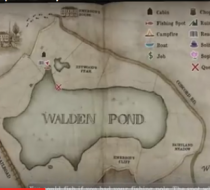

Instead of offering the thrills of stealing, violence and copious cursing, the new video game, based on Thoreau’s 19th-century retreat in Massachusetts, will urge players to collect arrowheads, cast their fishing poles into a tranquil pond, buy penny candies and perhaps even jot notes in a journal — all while listening to music, nature sounds and excerpts from the author’s meditations.

While the game is all about simplicity, it has actually been in development for nearly a decade. The lead designer, Tracy J. Fullerton, the director of the Game Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts, came up with the idea as a way to reinforce our connection to the natural world and to challenge our hurried culture.

“Games are kinds of rehearsals,” Ms. Fullerton said in an interview. “It might give you pause in your real life: Maybe instead of sitting on my cellphone, rapidly switching between screens, I should just go for a walk.”

Continue reading the main story

The game — which Ms. Fullerton said is likely to cost $19.99 — takes six hours to play. It starts in the summer and ends a year later — offering players tasks like building a cabin, planting beans or chatting, virtually of course, with Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Should you not leave sufficient time for contemplation, or work too hard, the game cautions: “Your inspiration has become low, but can be regained by reading, attending to sounds of life in the distance, enjoying solitude and interacting with visitors, animal and human.”

Failure to heed the warning will result in a dimming of color and thinning of music.

“You can choose how to spend your time, what to emphasize, the ways the game can play out,” she said. “You might spend all your time in the woods, you might focus on bean farming, you could become a famous author — sending off articles to your editor, Horace Greeley — or you could become an activist, working on the Underground Railroad.”

At a time when the most popular video games include the active participation of the player — slay a soldier to capture enemy territory — the Walden game seems passive by contrast. But Ms. Fullerton said it’s no simple stroll in the park. Players who fail to forage for food, for example, will start to faint in the game.

The goal is not to win in any competitive sense, but to achieve work-life balance.

“You’re not only trying to survive, you’re seeking inspiration in the woods,” Ms. Fullerton said, “If you spend all of your time grinding away on survival tasks, the environment will become less lush. The winning is based on whether you meet your own goals.”

The project has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, though some say video game research is unworthy of federal funds.

And some Thoreau experts are not enthused by an electronic simulation of Walden Pond. “Go out and see your own backyard,” said Richard Higgins, whose book, “Thoreau and the Language of Trees,” is to be published in April by the University of California Press. “Nature is all around us.”

But guardians of Thoreau’s legacy say it could introduce Walden to a whole new audience. “These are people who are interested in interactive games,” said Kathi Anderson, the executive director of the Walden Woods Project in Massachusetts. “Maybe they’re not the same as the people who would sit down and read Thoreau’s book.”

Ms. Fullerton — whose group also created the popular 2005 flying game Cloud — consulted Ms. Anderson’s organization, along with the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, to create the game. They went to considerable lengths to get the 1854 details right — the types of trees, the sounds of historically-accurate birds.

Would Thoreau approve? He was clear about dismissing new technologies, if this quote is any indication:

“Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys, which distract our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end, an end which it was already but too easy to arrive at; as railroads lead to Boston or New York. We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate.”

But Ms. Fullerton said the game — to be released this spring in time for the 200th anniversary of Thoreau’s birthday in July — re-examines the very questions “Walden” raises about the personal costs of progress.

“Thoreau was sitting in a moment when life was beginning to speed up and he identified that, asking ‘Are our lives better because we now live on railroad time?’” she said. “We have to ask ourselves the same question today: ‘Are our lives better because we live on internet time?’”

“Maybe we don’t all have the chance to go to the woods,” Ms. Fullerton added. “But perhaps we can go to this virtual woods and think about the pace of life when we come back to our own world. Maybe it will have an influence — to have considered the pace of Walden.”

By ROBIN POGREBIN

New York Times

FEB. 24, 2017