“Is it Real? Yes It Is!” Favorite

In recent years, a fashion for painting the human figure has preoccupied the art world, with an emphasis on race, gender and other urgent social issues. Yet another pressing topic in America has been curiously absent from art: abortion, which became all the more timely when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June.

Depictions of abortion are still rare in the art-history canon. Check the walls of museums and flip through the pages of H.W. Janson or other art textbooks, and you are likely to encounter countless images of beatific mothers, dimpled infants and a world in which pregnancies are not terminated.

But the subject of abortion, which historically was shrouded in shame and relegated to the realm of unspeakable secrets, has lately been gaining visibility in the art world. The change owes something to a mix of museum officials, blue-chip galleries, art fair administrators and young artists who grew up at a time when art that explored personal identity moved from the cultural fringe into the mainstream.

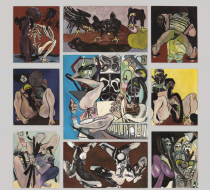

For 90 years of its existence, the Whitney Museum of American Art did not own a single painting that explicitly deals with abortion. But that has changed. The museum recently purchased Juanita McNeely’s “Is it Real? Yes It Is!” (1969), a mural-sized painting that recounts, in a fragmented narrative spanning nine separate panels, her harrowing experience of having an abortion in the early ’60s, when the procedure was illegal. The painting will make its museum debut on Sept. 20, when the Whitney rehangs its permanent collection.

Last weekend, the best place in New York to contemplate abortion-themed art was the lobby of the Armory Show, that annual fair whose thronged aisles of art shoppers can make Bloomingdale’s seem like an oasis of calm. It opened on Friday at the Javits Center, on an uncharacteristic note of feminist advocacy, thanks to a loan of 10 etchings that reprise Paula Rego’s now-historic “Abortion Series” (1998-99) from the Cristea Roberts Gallery in London.

The series consists of large-scale pastels that show women in the midst of self-induced, at-home abortions. They lie in rumpled beds or crouch in corners, amid towels and bowls and metal pails, cast off by a medical establishment unwilling to help them. As graphic as all this might sound, Rego, a celebrated Portuguese artist who died in June, at age 87, purged her images of potentially harsh bodily details. Her female figures remain clothed, and they tend to be shown from the side — they come across as daunting individuals with willful expressions and thickly muscled runner’s legs. “I tried to do full frontal,” she once said, “but I didn’t want to show blood, gore or anything to sicken, because people don’t look at it then. And what you want to do is make people look.”

Despite such instances of social protest, the issue of female reproductive rights has yet to receive the sustained attention that the art world has lavished on climate change and mass incarceration, among other timely issues. But then, abortion is a singularly discomfiting topic, not just among art institutions, but even among artists, a famously liberal bunch who overwhelmingly support legalized abortion. In recent interviews with female painters and sculptors, I noticed a basic tension between their sense of outrage over the dismantling of Roe and a caution about adopting the subject for their art. Art about abortion, some women say, risks becoming lurid, overly intimate, or politically naïve, converting sensibility into a slogan, and turning advocacy into a turnoff, which may partly explain the dearth of art on the subject.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the director, Max Hollein, who oversees a collection of 1.5 million objects, said he could not think of any art about abortion “off the top of my head.” But he would welcome the chance to look at art that “comes out of this moment.” He cautioned against expecting quick results. “At the end of the day, art is not journalism, and museums are not a daily medium that can respond in a timely manner.”

At the Brooklyn Museum, Anne Pasternak, the director, also referring to a collection that goes back to antiquity, said: “We have 150,000 objects in the collection, and I can’t think of one specifically about abortion.”

But in a spirit of advocacy, she emailed museum members on June 24, the day of the overturn of Roe v. Wade, warning that “we are facing a relentless assault on human dignity.” And curators are in early talks with the artists Jenny Holzer and Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter about staging “activations” at the museum in January to honor the 50th anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision by the Supreme Court.

Art about abortion is infinitely varied, shifting between Rego-style political activism at one extreme and raw self-exposure at the other. At the helm of the confessional mode is Frida Kahlo, the brilliant Mexican modernist who invented the tradition of visual oversharing. In the process, she legitimized female trauma as a subject for art.

The de Young Museum, in San Francisco, owns a rare abortion-themed work by Kahlo from 1936. A small, poignant lithograph, it is alternately titled “El Aborto” (in Spanish) or “Frida and the Miscarriage.” (Scholars disagree over whether it shows an abortion or a miscarriage; Kahlo is known to have had at least three pregnancies that she could not carry to term.)

In the lithograph, she depicts herself in a pose reminiscent of a woman in a medical textbook, facing front. A curled fetus is visible inside her womb. Two oversized tears run down her cheeks, and the moon above weeps, too. A second image of a fetus — this one expelled from her body — hovers in the lower left, while a heart-shaped palette on the right suggests that art is both consolation and surrogate for a lost child.

McNeely, the artist whose painting was acquired by the Whitney Museum, can be said to belong to Kahlo’s lineage of art-as-autobiography. Her “Is It Real? Yes It Is!” adopts an angled, expressionist style to chronicle a medical emergency that left her bleeding profusely and in critical condition before she found a doctor willing to disregard the law and perform an abortion that she believes saved her life.

Now 86, McNeely, who has lived for nearly a half-century in a studio in Westbeth, the artists’ housing complex in the West Village, was in high spirits when I visited her the other day. The Whitney purchase came as a great surprise, especially since her repeated efforts to exhibit the painting at a gallery were rejected until last year, when she was given a solo show at the James Fuentes Gallery. She attributes her decades of professional obscurity to a societal aversion to contemplating female trauma. “I had done a lot of paintings with blood,” she recalled. “I was big on blood. The more blood the better.”

Was she concerned about the potentially off-putting aspects of depicting an abortion.? “You wouldn’t be alive without your blood,” she countered cheerfully.

Do men make memorable artwork on the subject? At least one has. Ed Kienholz’s sculptural assemblage, “The Illegal Operation” (1962), at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was inspired by his distress over his wife’s abortion. Cobbled together from found objects — a lamp with a crooked shade, rusty tools, a shopping cart commandeered as an operating table — it imbues the site of an at-home abortion with almost unbearable forlornness.

But not every artist who favors abortion rights is interested in using art to advance the cause. Many of our most esteemed female artists — particularly those who lived through the pre-Roe era of illegal abortion — acknowledge an element of self-censorship on the subject.

Consider the much-anticipated group show, “Painting in New York, 1971-1983,” which opens at Karma, the East Village gallery, on Sept. 21. It will bring together the work of 30 prominent female painters who began their careers during the heyday of second-wave feminism. It will also raise money for Planned Parenthood by selling a T-shirt, a text-free object bearing an abstract painting by the artist Mary Heilmann that features a grid of nestling rectangles in fuchsia and bubble gum and other pink-related hues.

Revealingly, none of the works in the show pertain to abortion, according to its participants. “It is only recently that women have been willing to publicly acknowledge having had an abortion,” said Joan Semmel, a figurative artist and staunch feminist who turns 90 next month, by way of explaining why she never considered painting an abortion-themed work. “The translation of pain is always edgy, and emotional pain can be maudlin.”

The artist Lois Lane, who is also in the Karma show, emphasizes that she came of age at a time when art-world sexism was overwhelming. Having a career in art was enough of a professional challenge without highlighting her female status. “When I began my career, I felt like I was pushing a boulder uphill every day,” she said, “and the last thing I would have done is paint a picture of my ovaries.”

Even Kiki Smith, the pre-eminent sculptor of the female body, said that abortion is more interesting to her as a social topic than an art topic. Smith, 68, mentioned that she had an abortion when she was in her 20s. “Personally, that’s the most sorrow I‘ve had in my life,” she recalled, adding that the prospect of raising a child was not a possibility for her. “I just didn’t have enough of myself. There wasn’t enough of me to be able to care for someone else.”

A show of Smith’s body-themed sculptures from the ’90s will go on view on Oct. 19 in the artist Alex Katz’s personal gallery, at 211 West 19th Street. Not included in the exhibition is “Untitled,” 1989, a 4-foot-tall female figure, or rather the lower half of one, made from translucent paper and torn off at the waist. The sculpture emits a light, floaty feeling that contrasts with the fraught subject: A fetus dangles from a cord between the woman’s legs. Although the sculpture might seem to directly refer to abortion, Smith said she prefers to think of it as an expression of “my ambivalence about motherhood.”

Every generation of artists is shaped by its moment of entry onto the art scene, and there is much to suggest that younger artists today have a nimbleness with political content that eludes most of their predecessors. In a current show at the Matthew Marks Gallery, Julia Phillips, 37, an accomplished German American artist, treats the subject of abortion with a chilling, almost clinical frankness. The back room of the gallery is reserved for two sculptures, “Aborter” and “Impregnator,” in which an assortment of small objects resembling gynecological tools rest on steel trays, evoking a dystopia in which women surrender control of their bodies to unknown agents.

Phillips, speaking by phone, said, “I don’t think that without the experience of having an abortion I would have had the audacity to make a piece called ‘Aborter.’ There is an urgency to be more explicit, and it still comes with discomfort.”

Still, some of the most familiar art about abortion shuns visceral images of the body in favor of streamlined text. Barbara Kruger’s “Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground”), from 1989, has lately been appropriated on social media as the default icon of post-Roe discontent. Like much of Kruger’s work, the image combines an old found photograph with overlaid text. It starts with a slogan (“Your body is a…”) and imbues it with the mystery of art.

Who is the woman gazing from that photograph, that attractive brunette halved vertically into Manichaean contrasts of darkness and light? Kruger has not publicly identified the source. She originally created the image as a poster for a 1989 Women’s March. The posters are long gone, but a 9-foot-square version of “Your Body Is a Battleground” remains on view at the Broad museum in Los Angeles.

I called Kruger the other day to see what else she had planned. In keeping with her reputation for pointed aphorism, she exclaimed, “I’m fine. I have no complaints, except for the world.”