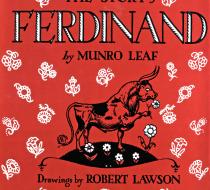

Ferdinand the Bull 1 Favorite

On a damp and rainy Sunday in October of 1935, Munro Leaf sat down to write a story. He had been eager to work with his friend – the illustrator Robert Lawson – for some time and so he decided to pen a book which he felt might suit the illustrator’s skills. Lawson was a master at drawing animals but horses, dogs, cats, rabbits and mice had all been done a thousand times already. Leaf wanted something new and decided that his story should be about a bull. What he created was called The Story of Ferdinand. It was a simple but amusing tale of a peaceful Spanish bull who had no interest in bullfighting.

Leaf was himself rather modest about the work; remarking once that he had written it in less than forty minutes. Yet once the words were combined with Lawson's beautiful black-and-white etchings, the pair felt quite satisfied with the outcome. Indeed, they even joked that their publication had the potential to go on and sell twenty-thousand copies. Two years later the book had sold more than twelve times that amount.

What was even more surprising was the reaction that the simple story was getting. In no time at all their picturebook was being labelled as subversive and it was stirring up all kinds of international controversy. Banned in Spain, burnt by Hitler and continuously dissected and deconstructed, The Story of Ferdinand remains, to this day, a fascinating example of the power of picturebooks.

Published by Viking Press in 1936, the release of Ferdinand came during the era of the Great Depression. For this reason, its initial release was rather modest. It seemed that their publisher was only mildly enthusiastic about it and so only one-and-a-half-thousand copies were originally published. That year also saw the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. In just nine short months after the book's release, Spain saw itself caught in a violent war between a right-wing group of Nationalists and the country's democratic, left-leaning government.

In light of these events, Ferdinand started to take on a much greater significance. Leaf and Lawson's book presented a Spanish character who stood out from society and refused to fight. Those who supported the violent uprising that was led by Francisco Franco viewed it as pacifist propaganda and they banned its publication. It wasn't until Franco's death in 1975 that this ban was eventually removed.

Despite the tendency for people to read a political message in the story Munro Leaf always maintained that its only agenda was to entertain. “It was propaganda all right,” he's quoted as saying, “but propaganda for laughter only.”

Even with all that said, people continued to draw their own meanings from the book. Clearly, Ferdinand is a story that celebrates the right for people to develop their own unique identities. Yet, to some, this message can be seen as dangerous when people don't conform to the mainstream or when they don't help to further a national agenda. Franco and his supports certainly saw it this way. So too did Hitler who apparently labelled it as “degenerate democratic propaganda”. During World War II he ordered that all copies be destroyed. After he was defeated in 1945, thirty-thousand new copies were quickly published and handed out freely to the children of Germany in the hopes of encouraging peace between nations.

Even with the controversy that surrounded it, the book managed to become a massive international hit and a cultural phenomenon. In 1938 it outsold Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind and it went on to become the number one bestseller in the US that year. Today it has been translated into more than sixty languages and has sold millions of copies worldwide.

Ferdinand had – and continues to have – many famous admirers. People like H.G. Wells, Gandhi and Ernest Hemingway all supported the book; while musician Elliott Smith sported a tattoo of the peaceful bull upon his arm. One year a giant Ferdinand floated down New York's Sixth Avenue as part of the Macy's Day Parade. On another occasion, the bull's story was turned into a song by the jazz duo Slim & Slam. Even Disney got involved, creating an animated adaptation of the story in 1938.

Much of its success must certainly lie in the fantastic pairing of Leaf's words with Lawson's illustrations. One account suggests that the illustrator loved the text so much that he managed to produce a complete "dummy" book on the same day that he had read it. Another account suggests that the illustrator was initially intimidated by the text, having never drawn a bull before or even been to Spain. And so for that reason, it may have taken him several months before he had researched enough to properly put pen to paper.

Whatever the truth may be, the book manages to transport its reader into Ferdinand's world effortlessly. The anatomy of the bulls are perfect and the costumes of the picadors, matadors and banderilleros all feel accurate. Yet these technicalities go unnoticed. What stands out is the beautiful interplay between the words and pictures. Ferdinand is a warm, good-natured and humorous book that is filled with inventive flourishes and a sharp rhythm that allow the text and image to carry equal importance.

A philosophical reader will certainly draw political themes out from this story, but many will argue that its true longevity has nothing to do with the possible metaphors within it. A young audience isn't drawn to The Story of Ferdinand because of its political parallels.They like the book because Ferdinand is an easy character to empathise with.

Another strength of the title comes from the fact that Leaf and Lawson don't patronise their young readers. “I have never, as far as I can remember, given one moment's thought as to whether any drawing that I was doing was for adults or children” Lawson once said. "I have never changed one conception or line or detail to suit the supposed age of the reader.” Perhaps this is the main reason for the book's survival.

Lawson felt that the terms "children’s author" and "children’s illustrator" were condescending. He believed that these titles suggested that an author or illustrator had to cater their work to fit the limited tastes or understandings of young readers. He believed that the opposite was, in fact, the case. He felt that children were less limited than adults.

“They do not know that they ought to admire certain art because it is ‘naive’ or ‘spontaneous’ or because it has been drawn with a kitchen spoon or a discarded shirt front,” he said. “They are, for a pitifully few short years, honest and sincere, clear-eyed and open-minded. To give them anything less than the utmost that we possess of frankness, honesty and sincerity is, to my mind, the lowest possible crime.”

Over the course of their careers, Leaf and Lawson worked together on one other title. It was a book set in Scotland called Wee Gillis (1939). It received great acclaim and was cited as a 1939 Caldecott Honor Book. In his lifetime Leaf wrote nearly forty titles and had a career that spanned forty years. Lawson too had a long and successful life as both illustrator and author. In 1945 he became the first, and so far only, person to be given both the Caldecott Medal (They Were Strong and Good, 1941) and the Newbery Medal (Rabbit Hill, 1945).

Yet it is their tale of Ferdinand that they will continue to be both best remembered for. More than three-quarters of a century on its message continues to resonate and Ferdinand's story is one that remains shared, loved and celebrated all over the world.

A Subversive Bull: Robert Lawson and The Story of Ferdinand

Philip Kennedy

December 1, 2016

Illustration Chronicles