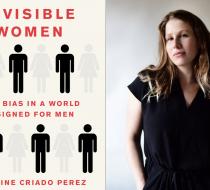

Invisible Women - A World Designed for Men Favorite

The problem with feminism is that it’s just too familiar. The attention of a jaded public and neophiliac media may have been aroused by #MeToo, with its connotations of youth, sex and celebrity, but for the most part it has drifted recently towards other forms of prejudice, such as transphobia. Unfortunately for women, though, the hoary old problems of discrimination, violence and unpaid labour are still very much with us. We mistake our fatigue about feminism for the exhaustion of patriarchy. A recent large survey revealed that more than two thirds of men in Britain believe that women now enjoy equal opportunities. When the writer and activist Caroline Criado Perez campaigned to have a female historical figure on the back of sterling banknotes, one man responded: “But women are everywhere now!”

It’s a smart strategy, therefore, to invite readers to view this timeworn topic through the revealing lens of data, bringing to light the hidden places where inequality still resides. Criado Perez has assembled a cornucopia of statistics – from how blind auditions have increased the proportion of female players hired by orchestras to nearly 50%, to the good reasons why women take up to 2.3 times as long as men to use the toilet. This is a man’s world, we learn, because those who built it didn’t take gender differences into account. Most offices, we learn, are five degrees too cold for women, because the formula to determine their temperature was developed in the 1960s based on the metabolic resting rate of a 40-year-old, 70kg man; women’s metabolisms are slower. Women in Britain are 50% more likely to be misdiagnosed following a heart attack: heart failure trials generally use male participants. Cars are designed around the body of “Reference Man”, so although men are more likely to crash, women involved in collisions are nearly 50% more likely to be seriously hurt.

One woman reported that her car’s voice-command system only listens to her husband, even when he's in the passenger seat. Gender-blindness in tech culture produces what Criado Perez calls the “one-size-fits-men” approach. The average smartphone – 5.5 inches long – is too big for most women’s hands, and it doesn’t often fit in our pockets. Speech-recognition software is trained on recordings of male voices: Google’s version is 70% more likely to understand men. One woman reported that her car’s voice-command system only listened to her husband, even when he was sitting in the passenger seat. Women are more likely to feel sick while wearing a VR headset. Another study found that fitness monitors underestimate steps during housework by up to 74%, and users complain that they don’t count steps taken while pushing a pram.

Even snow-ploughing, it turns out, is a feminist issue: in Sweden, roads were once cleared before pavements, a policy derived from data that prioritised commuters in cars over pedestrians ferrying children or doing the shopping. But then officials realised that it’s easier to drive through three inches of snow than push a buggy through it. Clearing pavements first also saved the state money: a study in one Swedish town found that pedestrians were three times more likely to be injured in icy conditions than car drivers; and 70% of those injured were women.

The sheer abundance of examples in this book militates somewhat against its argument, which is that there is a lack of gender-specific data: a “gender data gap”. Googling “gender impact assessment” yields upwards of 345m results. Criado Perez to some extent acknowledges this tension, imploring planners and politicians to make better use of the data that already exists, but that’s less an issue of data than of policy and design.

The neat thing about data is that it avoids thorny questions of intention. Criado Perez doesn’t set out to prove a vast conspiracy; she simply wields data like a laser, slicing cleanly through the fog of unconscious and unthinking preferences. Unless we crunch the numbers and take positive steps to correct bias, she argues, inequality will automatically continue. Technology is associated with innovation, but algorithms tend to reinforce the status quo: “If you like that, you’ll love this.”

Data not only describes the world, it is increasingly being used to shape it. The first programmers were women – the human “computers” who performed complex calculations for the military during the second world war. Now women make up just 11% of software developers, 25% of Silicon Valley employees, and 7% of partners at venture capital firms. Bytes may be neutral, but programmers are often – wittingly or unwittingly – biased.

Given the growing power of those algorithms, I wanted to find more about what Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism” – the myriad ways in which the “internet of things” and social media are selling our private lives to advertisers. The data predicting and moulding our behaviour is granular enough to know the percentage of cashmere in the sweater I bought online last year in a weak moment, and it certainly knows I’m female. The problem with this kind of micro-profiling is not its gender data gap but its ruthless commercialisation of everyday life – although women, under constant pressure to be Instagram-ready and fashion-forward, are arguably its disproportionate victims. By calling out persistent unfairness in a world that – for all the talk of technological “disruption” – seems to have given up on the idea of human progress, this book ends up treading more familiar ground than the data theme may initially suggest. Campaigning may rely on saying the same thing over and – wearyingly – over again. For this, our stubbornly sexist society, not its doughty critic, is to blame.

-Eliane Glaser, Feb 28, 2019. The Guardian.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/feb/28/invisible-women-by-carolin...