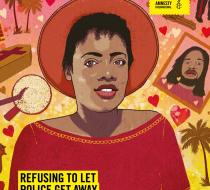

Police Shot Her Brother. Now She's Fighting for Justice. Favorite

Police in Jamaica kill three people a week with impunity. But one woman, Shackelia Jackson, is determined to get justice for her murdered brother.

Shackelia Jackson’s email signature reads, “Broken, not Destroyed.” After her brother Nakiea was shot by police in 2014, Jackson has spent years fighting for justice for him and other victims of extra-judicial killings.

On January 20, 2014, 29-year-old Nakiea Jackson was at a restaurant in the Orange Street Villas neighborhood of downtown Kingston, where he worked. At around lunchtime, Jackson says, a police officer entered the restaurant and eyewitnesses heard two gunshots fired. Police believed a robbery had happened nearby, and were looking for a “Rastafarian-looking” man—like Naikea. (Shackelia tells me that her investigations have not provided any evidence of a robbery taking place in the area.)

Hearing people shout Naikea’s name outside her house, Shackelia ran to the restaurant where her brother worked. Outside was a frantic, emotional crowd. Upon entering the restaurant, she saw blood. “I immediately realized the worst had happened,” she says. After locking the restaurant in an attempt to preserve what was left of the crime scene, she rushed to the hospital.

“When I arrived I saw doctors working to save him,” the 35-year-old remembers. “As he was being wheeled towards me on a gurney, I told him ‘I love you,’ hoping he would hear.” At around 4:20 PM that day, Naikea was pronounced dead.

“He was wearing an apron, bearing an ID that declared him as a chef, and there was chicken in the deep fryer,” she says. “But with my brother being a Rastafarian, that was sufficient to ignore his right to life. Because of an egregious error at the hands of police, Nakiea became a statistic.”

At the time of publication, INDECOM—the Jamaican commission for investigations—had not provided a comment or the police report into Nakiea's death, despite repeated requests to do so.

Since her brother's killing, Shackelia has become an outspoken force against against police killings, especially for those most at risk: young men and teenage boys, typically from inner-city, low-income neighborhoods. Amnesty International reports that in 2015, eight percent of all Jamaican killings were at the hands of police. Although rates of extra-judicial deaths have declined in recent years, it remains the case that police stigmatize and criminalize predominantly impoverished communities as part of a strategy to “get rid of criminals.”

“For decades, Jamaican inner city neighborhoods have been scarred by an epidemic of unlawful killings by the police,” explains Louise Tillotson of Amnesty International. She tells me that, in 2017, Jamaican law enforcement officials killed an average of three people a week—168 people, according to INDECOM. “But numbers only tell part of the story. Not only has the way police operate and unlawfully kill not changed in 20 years, but too often police go on to violate the human rights of surviving relatives.”

For women like Shackelia, achieving justice is an unremitting slog. “Victims’ families, particularly women relatives, are left to battle a sluggish court system, and frequent harassment and intimidation by the police which aims to stop families from pursuing justice.”

In the days and months following Naikea’s death, Shackelia publicly searched for answers—but received none. She made independent investigators secure the crime scene, and pursued his case through Jamaica's courts. But this came at a cost. Amnesty International reports that frequent police raids on Naikea’s downtown Kingston neighborhood often coincided with days where the courts were due to hear his case. When his community protested his case being dismissed in July 2016, police cars turned up. And Shackelia tells me that Naikea's supporters have been intimidated and harassed by police.

“They’ve maintained the code of silence and brotherhood,” she tells me, saying that she’s been subjected to police raids and wrongful arrests. Shackelia believes that justice for Naikea hasn’t been forthcoming because the structural forces at work are so powerful: admitting culpability would set a costly precedent, and disrupt the narrative that Jamaican law enforcement use to justify their extra-judicial killings. “[These deaths] are too common,” she says. “They’re the order of the day.”

For now, Shackelia will continue fighting for justice for Naikea and all the other victims of Jamaican police brutality. “I can’t stop,” she tells me. “I have to become Naikea’s voice. I have to preserve his legacy.”