Zone à Défendre, or “zone to defend” (ZAD) Favorite

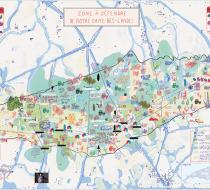

The ZAD (zone à défendre, or “zone to defend”) in Western France is 4000 acres of wetland, farmland and forest that was originally intended to be built into an airport in 1965 but is now an autonomous territory occupied by 40 different collectives looking to reclaim the land. There are around 200 people living permanently on the zone, in addition to some 2,000 people coming and going. With its bakeries, surrealist vernacular architecture, pirate radio station, tractor repair workshop, brewery, banqueting hall, medicinal herb gardens, a rap studio, dairy, vegetable plots, weekly newspaper, flour mill, library and even a full working lighthouse, the zad has become a concrete experiment in taking back control of everyday life. Vegetables and fruits, flour and bread can all be found at the “non-markets,” where these products are given away for free or in exchange for a voluntary contribution, called a prix libre. Wholesome meals are prepared and served every time larger meetings and rallies are organized, and any newcomer will certainly find a space to sleep in one of the several dormitories. The different sections of society that have gathered around the struggle at the ZAD have a clear objective: building a world without states and beyond capitalism. The ZAD has a rich history of activism, rebellion and direct action. It is an entanglement of resistance and art, imagination and autonomous zones, living utopias and political systems.

In response to the airport proposal, local residents read out a letter declaring that “to protect and defend a territory, you need to inhabit it”. They called on groups to support the cause and squat in the empty farms and forests as an act of resistance.

In 2012, the French state tried to evict the zone, which consisted then of 40 to 50 local farmers who were refusing to sell their farms. Battling against riot police, the people resisted fiercely with songs and tractors. People were fighting from trees, they were burning barricades and they were even using Molotov cocktails. The residents claimed that even if an eviction were eventually successful, they would just come back. And they kept to their promise, 40,000 people turned up a month later to rebuild what was destroyed by the police. In three days, they had completed the reconstruction, but the police returned again, with tear gas, explosive grenades and rubber bullets, injuring 300 people.

The attacks only stopped after medical professionals sent a letter to the President urging him that people would die if this fighting continued. And for a while, the residents of the ZAD lived a life without police, without a government, without state planning and control.

In the aftermath of the decades of fighting, and as the dust is settling, it’s clear that resistance has not been so clear-cut. There were victories—after all, the airport was never built, the land was never left unoccupied—but there were also failures. This absence of a perfect utopia is not a reason to despair. In fact, it’s something to celebrate, because that means we can, and have been, building new worlds, as we speak.