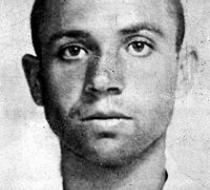

Miguel Hernández (Orihuela, Spain 10/30/1910 – Alicante, Spain 03/28/1942), life and death of a poet and activist Favorite

Miguel Hernández was a spanish shepherd, poet and playwright that dedicated most of his works to dignify the poor peasants of the rural areas of Spain.

He was born in Orihuela in 1910, and went to school until the age of 15. By that time, and due to his father's insistence, he started working as a goat shepherd. However, he didn't stop reading, and with the help and support of the canon Luis Almarcha Hernández and with frequent visits to the public library, he became a self-taught poet.

Some of his works got published in different magazines and journals, so he decided to travel to Madrid to consolidate his writing career. Even though this attempt didn't yield results, he got to meet other poets from the Generation of 1927, a group of spanish poets that stood out for the quality of their works and their commitment to social justice.

He got to publish his first book, Perito en Lunas, in 1933. It became a success, which allowed him to travel to Madrid. This time he managed to work for different magazines, becoming a figure in the blossoming literary scene of Madrid. A closer contact with the Generation of 1927, and his relationship with the painter and activist Maruja Mallo influenced him to make his work more compromised with the social situation in Spain. For example, he started working for the Misiones Pedagógicas (Educational Missions), an initiative promoted by the Second Spanish Republic to bring literature, theater and cinema to isolated villages.

To understand the importance of his commitment with the rural world it is necessary to at least have a quick overview of the spanish social structure during the 30s. In a country where more than 40% of the population was illiterate, more than 50% of the population lived in rural areas, and there were more than 2 million of peasants that didn't own any land and had to work for landowners for miserable wages, it is safe to say that the majority of the population lived under extremely hard life conditions. Poverty, hunger and poverty-related diseases were part of the daily lives of the majority of spanish people.

When the Civil War started, Miguel Hernández enrolled the Ejército Republicano (Republican Army) and the Partido Comunista de España (Communist Party of Spain). He fought in different battles in Teruel, Andalucía and Extremadura, with a quick break to marry Josefina Manresa. He also went to the Congreso Internacional de Escritores Antifasctista (International Congress of Antifascist Writers) that took place in Madrid and Valencia in the summer of 1937. He also traveled to the Soviet Union to represent the Spanish Republican Government.

During the war he published his play Pastor de la Muerte (Death Shepherd) and numerous poems that would later constitute his postume book El hombre acecha (The man stalks). In the meanwhile, he wrote journal articles from the trenches to exhort the republican troops. He also writes Viento del Pueblo (The Wind of the People), his most celebrated book.

His first son was born in 1937, but he died a few months later. The poem Hijo de la luz y de la sombra (Son of the light and the shadow) and other poems in his Cancionero de Ausencias (Anthology of Absences) are dedicated to his memory. His second son was born in 1939, only a few months before the Republican Army was defeated.

Miguel Hernández was captured and handed over to the Guardia Civil by the portuguese police when he was trying to escape from the francoist regime, that had tried to destroy all the exemplars of El hombre acecha (except for two, which allowed the book to be published in 1981) and had declared him an enemy of the new order. He is incarcerated in Seville, and from jail he writes his famous Nanas de la cebolla (The Onion Lullabies), dedicated to his second son after his wife told him in a letter that all she had to feed herself was bread and onions. He was transferred to Madrid and, thanks to Pablo Neruda, who interceded for him, he was released from jail.

He went back to Orihuela, his hometown, where he was denounced and arrested. He was taken back to prison in Madrid, taken to court and sentenced to death in 1940. His friends, including his old mentor Luis Almarcha Hernández, got to convince the francoist authorities to commute his death penalty for thirty years of imprisonment. He was transferred to Palencia, then to Ocaña (Toledo) and finally to Alicante, where he shared his cell with Antonio Buero Vallejo, another playwright. He got bronchitis and, shortly after, typhus and tuberculosis. He died at the prison's infirmary in March 28th of 1942, when he was only 31 years old. According to the legend, they never managed to close his eyes.

He was buried in the niche 1009 in the cemetery of Nuestra Señora del Remedio de Alicante two days after his death, but his remainings were exhumated in 1986 and buried again in Alicante, where he now rests with his wife. In 2007 the sentence that condemned him to imprisonment was declared illegal and illegitimate by the Ley de Memoria Histórica (Historical Memory Act).